[NOTE added 27 February 2014: There is NO scientific evidence that a positive feedback has kicked in. While methane levels are high (and increasing), they would have to be much, much higher to trigger "runaway global warming". Scott Johnson de-bunks the claims of a "methane emergency" (and the subsequent extinction of the human race by 2035) in this well-argued post].

A while ago, I looked into cars that run on compressed natural gas. Natural gas is cheap. It has been touted as a "clean" source of energy - anyway cleaner than coal. The burning of natural gas does not release soot particles that post a health problem; in addition, generating energy from natural gas releases less carbon dioxide, a greenhouse gas that causes global warming.

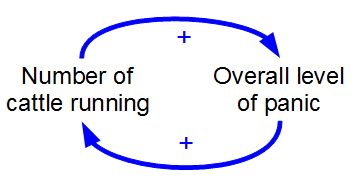

At least, that's the argument given by proponents of hydraulic fracturing, or "fracking" of gas-containing shale. But methane (CH4), the main component of natural gas, is itself a greenhouse gas, and one that is much more potent than carbon dioxide. Its global warming potential is usually quoted as GWP=25.

What that means is that methane is 25 times more effective at trapping heat than carbon dioxide, over a period of 100 years after its release into the atmosphere: GWP(methane, 100yr) = 25.

So, if methane is really to be a "clean" (meaning low-GWP) source of energy, there had better be no leaks: not around the rigs where the fracking happens, not in the pipelines that take that natural gas to power plants and homes.

But methane does leak.

This is not the ideal world, and as any homeowner knows, sooner or later some pipe in the house will leak.

The leaks around a fracking field can be as high as 9% of the recovered methane. That's enough to make natural gas a much less "clean" fuel, in the context of global warming, than coal.

Pipelines to users, exposed as they are to varying temperatures, vibrations, aging, and other realities, leak also. A team of scientists have taken a natural gas sniffer along roads all over Boston, MA, looking for any leaks. The picture is not pretty.

Image by Kaiguang Zhao of Duke University

In the image, the height of the spikes indicate the methane concentration at that location. Yellow indicates a concentration higher than 2.5 parts per million. In Cambridge, you can see Harvard and MIT light up.

_at_Avenue_Louise,_Brussels,_Belgium.jpg/800px-Zencars_(Tazzari_Zero)_at_Avenue_Louise,_Brussels,_Belgium.jpg)