CelloMom on Cars

The quest for the fuel-efficient car that fits the planet and the budget - and the cello.

July 25, 2023

Farming for cars

July 22, 2023

Energy efficiency: gasoline, electric, and hydrogen car

June 17, 2023

Battery powered locomotives

May 18, 2023

Norway's new tack on the EV

August 10, 2022

This EV uses a tiny amount of lithium in its battery

August 9, 2022

Inflation Reduction Act

February 13, 2021

Cop Shows Without Car Chases

One year into the COVID-19 pandemic, we've learned more about virus biology than we cared to know; done more zoom meetings than we wanted to sit through; learned that, when society gets turned upside down, a few ugly things come to light; re-discovered our bikes; and binge watched shows. It's been quite a year, and the lucky ones among us have spent much of that year at home.

Like many others, I discovered Korean tv shows. It's like going on a holiday, but from your own couch: you get to struggle with the language, even if only passively, and learn about the culture a little bit.

It's different. For starters, people address each other by their full names, family name first. It's a change from Japanese shows where characters address each other by the family name only. But I suppose in a place where there are only so many last names you have to add the given names - I am told that the Korean version of looking for a needle in a haystack is "looking for Mr Kim in Seoul".

It seems Asians in general have only recently discovered the kiss. They don't even have their own word for it, apparently: in Korean romantic comedies they use the English, "kiss" (pronounced "kis-su"). You can tell it's novel because a kiss tends to be shown with a dramatic sweep of the camera, and usually at least three times, from different angles. At first it takes you by surprise, then it's hilarious.

Scene from Tunnel, in which the very manly main characters both cry often.

There is this myth around of the inscrutable Asian, but many Korean shows depend on the close-up; the changes in facial expression carry the emotional story of the show. One of the important emotions is sadness, and Korean characters of both sexes show that, by crying. In Mystic Pop-Up Bar the stories revolve around the dead, so it's unsurprising that there's a crying man in just about every episode. But even cop shows (The Good Detective, Tunnel) feature men who are man enough to cry.

The product placement is shameless. I'm clueless about Korean brands, but learning fast because you just can't not see it. And you can't miss the placement of western brands, like when every one of the main characters in Itaewon Class starts driving a Mercedes.

Fights are different too. The typical Western hero hardly ever suffers a beating, but when he does take a hit, he bounces right back up, every hair in place, to deliver the retaliatory blow. Asian characters don't have that kind of teflon: one hit on the jaw (sometimes not even on the jaw) and there's blood on the lips. Fights don't look clean at all, they're more like scuffles, and somehow feel more realistic.

Scene from Stranger, where the getaway vehicle is a bicycle, subsequently discarded as the culprit jumps over a balcony. The cops in hot pursuit are, of course, on foot.

Here's another feature that you can't miss: Korean cop shows have no car chases. Occasionally there is one, but in most chases, the culprit tries to get away by jumping over walls and sprinting down ways barely wide enough for two bicycles to pass each other, let alone a car. Shows set in Seoul also tend to have chases on very hilly streets. The music is pumping, your heart is pumping, but instead of the cop or the culprit shown madly turning the wheel or - in European chases - gamely changing gears, this chase is all about whose lungs and legs win out. It's cool and refreshing!

You may also like: 1. Measuring Loss in Terms of Human Suffering, Not Dollars 2. The Car as Apocalypse Meter: Bread Line 3. Why Bicycle Riding Is Good For Democracy

February 9, 2021

EV: no catalytic converter required

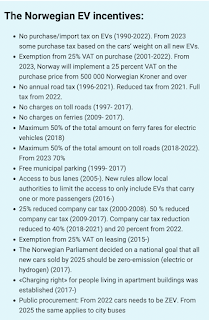

Superbowl 2021 featured an ad for GM's EVs. It's got Will Ferrell, Kenan Thompson and Awkwafina traveling – separately, getting lost in different countries – to see what's up with Norway's success in getting electric cars on the road, and how come they're ahead of the United States.

Spoiler: as Robinson Meyer points out, "EVs command 54 percent of the market share in Norway not because Norwegians love Tesla, but because Norway has thrown a small fjord’s worth of incentives and mandates behind them."

I suppose if you're GM, you don't want to remind anyone that until quite recently you threw your considerable clout behind fighting federal mandates that would promote EVs. You focus on the made-in-America thing, the patriotic thing, the masculinity thing, even if what we're talking about here is electro-masculinity.

I want to see an ad that makes fun of the fossil-fueled, horsepower worshipping masculinity. Pitting, say, a mom bringing her kids to soccer practice without mishap in her EV, against her neighbour with the gasoline powered muscle car who gets stuck in his driveway because his catalytic converter has just been swiped for the precious metals it contains. The tag line for the EV: "No catalytic converter, no tears".

As catalytic converter theft has been rising dramatically, people would recognise the consternation you feel at realising that you can't get ouf of your driveway. Not to mention that it takes upwards of two thousand bucks to get your gas-driven vehicle to carry you around again. In contrast, an EV has no tailpipe pollution, so it doesn't need a catalytic converter.

The irony is that the Prius, that symbol of the clean drive (before EVs came along that is), is one of the cars most vulnerable to losing its catalytic converter to theft. My brother finally had to let go of his twenty year old Prius, after the second time its catalytic converter was stolen. The catalytic converter is just about the first thing you see when you crawl under a Prius; also it's shaped like a tardigrade so it's irresistibly adorable.

No wonder people are now selling covers that make it harder to take off the catalytic converter.

You may also like: 1. Measuring Loss in Terms of Human Suffering, Not Dollars 2. How to buy a gas sipper for less 3. Extreme weather and the migration of drivers' licences

April 12, 2020

The Car as Apocalypse Meter: Bread Line

In the United States of the late 20th century and the beginning of the 21st, the car is ubiquitous. It dominates the roads. It makes its presence known. We know its speed, its smell, its size.

And that is why the car is used as a yard stick to measure things by. In a disaster, the car is used to convey the scale of that disaster in terms most people can understand. Think of the image of the yellow taxis in New Jersey, submerged in muddy water halfway up the windows following superstorm Sandy.

The coronavirus pandemic has brought lockdowns, and the lockdowns have brought traffic to a halt all over the planet. People are gushing over the long-range views, the blue sky - "Positively Alpine!" -in places that usually choke in deadly air pollution, the silent killer we have learned to live alongside, more of less successfully ignoring its fatal effects.

The absence of the car is disconcerting, gives freeways and thoroughfares a funereal, apocalyptic feel. Instead, we find the car re-arranged in new formations.

On April 9, 2020, the San Antonio Express News published an article on the line that formed at the San Antonio Food Bank. In the old days, breadlines were lines of people. The scale was human, and this is what made an impression. But the bread line of 2020 is a line of cars.

People queued up in their cars to preserve the physical distancing that limiting the spread of the virus called for. In San Antonio there were 10,000 cars lined up, its drivers waiting for hours to receive food after they had been laid off in the vast shuttering that had taken place throughout the country.

The number 10,000 is just a number. But an aerial photo of the cars, lined up in orderly rows, brings home just how many people were collecting that donation of food, on that hot day in Texas.

And I wonder what happened to the people who needed food but didn't have a car.

You may also like:

1. Measuring Loss in Terms of Human Suffering, Not Dollars

2. How to buy a gas sipper for less

3. Extreme weather and the migration of drivers' licences

August 10, 2019

Equity First

We humans have a fine nose for fairness, or lack thereof. Even before they learn about fractions in school, children can tell whether or not a pie is equitably divided. So if you're trying to propose a plan that makes things less equitable, you'd better have a convincing story.

Reagan's "A rising tide lifts all boats" was one of those stories. The 1980s rang in an era of rising inequality not seen since the Roaring Twenties.

This is true globally as well: the global version of Reagan's story was that globalisation would lift all boats, including those in developed countries. It did work out that way, but only for selected countries, like South Korea. In general, globalisation has caused the playing field for the accumulators to expand, so that now a handful of people - 26, to be precise - owns literally half the wealth in the world.

What did the rest of the world get out of it?

August 6, 2019

Low-Carbon High Rise Buildings? Bring It!

The skyscraper was the twentieth-century symbol of power and success, forming the highrise jungle of successful cities like New York, and copied in Hong Kong, Sao Paulo, Dubai, Kuala Lumpur, Beijing, and a long list of cities arriving into the fast growing global club of movers and shakers.

Most modern skyscrapers are of the steel-and-glass construction pioneered by the architect Mies van der Rohe. Here's one example: the building that houses the Department of Electronic Engineering, Mathematics and Computer Sciences at the University of Delft.

Its still a handsome building to look at. But its windows, facing east and west, catch the sun very efficiently and turn the place into a giant greenhouse. A very long time ago, as a physics freshman, I used to take an introductory electronics lab on some high floor on afternoons, but nobody ever enjoyed the view as the teaching assistants always kept the shades down and closed as tightly as possible. Even so, I sweated over those labs, and not just because I wasn't all that good at electronics.

As it was a fall course I never did find out how the building did in winter, but since it was constructed before double-pane windows were a thing, my guess is it could get pretty cold on the side that was not in the sun, which was at least half the place.

What I'm getting at is that climate control in this type of building is an energetic nightmare, even in the kind of temperate climate Mies van der Rohe hailed from. I shudder to think of the carbon footprint required to keep highrise livable in places that get cold, like Toronto, or that get super hot, like Dubai.

Yet here is New York, a place that gets both cold winters and hot summers, whose climate action plan calls for its buildings to cut their carbon footprint by 40 percent by 2030, which is only a decade away. On the other side of the continent, Vancouver's glass towers are said to undercut the cities nice climate action plan.

What to do?

August 2, 2019

Holiday Travel in the Age of Climate Change

When I was growing up, come the summer holidays my parents would pile our stuff in the VW van that my dad had converted into a camper, and drive around Europe for four to six weeks. They always took care not to leave on the vacation rush: that weekend when half the Netherlands seemed to start their holidays, and highways to sunnier destinations could be congested for literally hundreds of miles.

In fact, "Black Saturday" is still a thing. It's on today for France, where there is a warning out not to travel unless you really have to, especially on the roads around popular destinations like Bordeaux. There's a total of 800 km (500 miles) of stuck traffic on French highways.

These days, vacation travel is hard for other reasons as well. A few years ago, we had to cancel a trip due to heat: I had been watching the weather forecast at our destination, and each day in the week before our departure the predicted temperature kept rising. The night before we were to get on the train, the forecast called for 38C (100F) temperatures.

Reader, we cancelled the entire trip.

We were lucky that our reservations were refundable (except the first leg of the train, as we made the decision within 24 hours of departure). Since then, we've made sure that our holiday reservations are of the cancellable type, even if doing that costs more.

This summer, that really worked out. Temperatures were coming down after two heatwaves that hit western Europe hard. Things were looking good. But then, a few days before our departure there was an intense, record-breaking heatwave. We took my aunt to cool off at Ikea, and started watching the weather and the travel advisories.

Rail operators started to report trouble on the lines: there were disruptions in the electricity supply or mechanical issues. Thalys, the high-speed operator, was briefly even forced to close ticketing.

This is travel in the era of the climate crisis: you need to monitor whether you can actually make that trip. We cancelled our hotel reservation. We discussed flying, but only briefly. My family knows I'm, putting it mildly, not in favour of short haul flights. Anyway, flights were being disrupted by thunderstorms at our destinations, so that was that.

In the end, on the morning of our departure we made a decision to take a chance, and we did make it without delays and without getting trapped in a hot train car. We made hotel reservations from the train (yay for WiFi on the rails!) Then we had a good time exploring, using the local public transport cards. We haven't had a car vacation in years, and don't miss sitting in the kind of holiday traffic that's out there today.

You may also like:

1. Why I Love High-Speed Trains

2. My Big Fat Dutch Wedding

3. How Will You Travel for Thanksgiving?